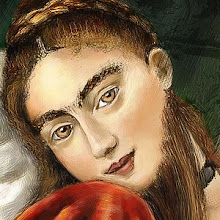

Most people would never go near a city during a plague outbreak, but on July 12th, 1624, the great portrait painter, Anthony van Dyck feared nothing in his quest to reach Palermo, Italy. The 25 year-old virtuoso had a very important meeting with a prominent noble woman and was determined to paint her portrait. (The portrait he completed from this meeting is below.)

Most people would never go near a city during a plague outbreak, but on July 12th, 1624, the great portrait painter, Anthony van Dyck feared nothing in his quest to reach Palermo, Italy. The 25 year-old virtuoso had a very important meeting with a prominent noble woman and was determined to paint her portrait. (The portrait he completed from this meeting is below.)

During the visit, van Dyck listened reverently as the old woman spoke of her bygone days as a lady-in-waiting in Philip II’s Spanish court. She squinted up at the young painter, trying to focus her half-blind eyes on his form, and advised him not “to get too close, too high or too low” because it would bring out the shadows in her wrinkles. (1) Van Dyck, grateful for her tutelage, recorded it diligently in his sketchbook—the only page to contain words.

Did this 96-year old bitty really have the right to give painting tips to one of the most talented portrait painters of the 17th century?

She most certainly did. For Van Dyck’s subject was not some crotchety, geriatric patron recording her portrait for posterity. She was Sofonisba Anguissola, one of the greatest portrait painters of the Renaissance.

Sofonisba was born in Cremona, Italy around 1532, in an age when most women were tied to a spinning wheel instead of a canvas. Believed to posses "a male soul that had been born in one of female sex," female artists were the bearded ladies of their day. (2) Yet, from a young age Sofonisba showed a spirit for painting that transcended what her contemporary John Knox identified as women's "weak, frail, impatient, feeble, and foolish" nature.

Sofonisba was born in Cremona, Italy around 1532, in an age when most women were tied to a spinning wheel instead of a canvas. Believed to posses "a male soul that had been born in one of female sex," female artists were the bearded ladies of their day. (2) Yet, from a young age Sofonisba showed a spirit for painting that transcended what her contemporary John Knox identified as women's "weak, frail, impatient, feeble, and foolish" nature. We can thank Sofonisba's father for his daughter's artistic education. Amilcare Anguissola was not your typical Renaissance dad. He encouraged all six of his daughters to develop their artistic, musical and language talents. Educating daughters was not unheard of in the 16th century, but it was certainly not common. Moreover, painting was not considered a profession for nobility because painters were still viewed as craftsman. (Michelangelo's father railed at him for becoming a painter.) Highborn ladies simply did not paint. Needlework was fine. Music part of a lady's polish. But mixing paint was for paupers.

Yet despite this social bias, Sofonisba's art education flourished in Bernardino Campi's studio when she was just fourteen years old. Typically, a painter would be apprenticed to a master for about five to seven years. During that time, the painter would learn how to mix pigments, prepare the canvas or panel, basic drawing skills and do many, many nude male studies. Similar to today's art foundation, learning how to the paint the nude body was de rigueur for any developing artist. As a woman, Sofonisba would never be given this foundation, but would instead have to rely upon what she knew of her own anatomy. I have often wondered if Sofonisba and her sisters would have dared to paint each other nude in private the way Michelangelo and Leonardo secretly painted cadavers?

One of Sofonisba's first assignments under Campi was to copy his Pieta. (shown here). Even at a young age Sofonisba was developing her own style. There is some of Leonardo's smoky background, and Campi's strong chiaroscuro, but Sofonisba's interpretation of this popular subject seems more doleful or delicate and her dark background forces the viewer to focus on the emotion in the painting.

One of Sofonisba's first assignments under Campi was to copy his Pieta. (shown here). Even at a young age Sofonisba was developing her own style. There is some of Leonardo's smoky background, and Campi's strong chiaroscuro, but Sofonisba's interpretation of this popular subject seems more doleful or delicate and her dark background forces the viewer to focus on the emotion in the painting.In 1549, Campi moved to Milan and Sofonisba then studied under Bernardino Gatti for about three years. She then left for Rome where she met the rock star of Renaissance painting - the aging Michelangelo Buonarroti.

Michelangelo's Art Challenge

Michelangelo's Art ChallengeMany of the great masters like Michelangelo would circulate their sketches to be copied by other artists and admired by patrons. According to a letter from Michelangelo's friend, Tommaso Cavalieri, Michelangelo, had seen a drawing done by Sofonisba of a smiling girl, and "said that he would have liked to see a weeping boy, as a subject more difficult to draw." (3) Sofonisba took up Michelangelo's challenge and sketched the picture above of her little brother, - Asdrubale being bitten by a crab. This sketch was greatly admired and became part of Vasari's collection of drawings, Libro dei disegni and would later inspire Caravaggio's Boy Being Bitten by a Lizard. Sofonisba's completed painting is below.

After her stay in Rome, Sofonisba left for Milan and continued getting commissions for portraits as her reputation grew. One of these commissions was to paint the Duke of Alba (this paintng is lost). Alba was so impressed with Sofonisba's work that he commissioned three more portraits and recommended her to Philip II of Spain.

Then Tudor history changed the course of Sofonisba's life when Philp II's wife, Mary Tudor died. Philip's second marriage was arranged with Elizabeth of Valois, (later to be called Isabel) the daughter of the French king Henri II and queen Catherine de Medici. To celebrate their wedding, a tournament was arranged with several festivities to follow. But during the joust, Henri suffered a wound to the eye and died. Suddenly, Elizabeth was journeying to a new country while grieving her father. The Duke of Alba recommended Sofonisba as a lady-in-waiting to Elizabeth, probably knowing the new queen would be lonely in the somber Spanish court. Elizabeth was also learning how to paint and Alba knew that Sofonisba's instruction would be a comfort to her.

At 27, Sofonisba was a veritable spinster when she became a lady-in-waiting to the new queen of Spain. It was odd that her father had not arranged a marriage for her by this time. Perhaps Amilcare could not afford a dowry. Or perhaps Sofonisba shared the same beliefs toward marriage as her teacher, Michelangelo who said of his art, "I have only too much of a wife in my art...and she has given me enough trouble." (4) In an age when many women died in childbirth, a spinster's life may have seemed like a more glorified path for someone of such immense talent.

Unfortunately, little is known about Sofonisba's time in the Spanish court because so many of her paintings have been destroyed in fires or have been attributed to other painters over the years. Sofonisba gave the young queen painting lessons, played the clavichord with her and was responsible for ordering fabrics. During this friendship, Sofonisba painted Elizabeth of Valois (shown here). Many of Sofonisba's painting (including this one) have been attributed to Philip's court painter, Alonso Sanchez Coella and several portraits are still in debate.

During the Renaissance, it was customary for a portrait to be made by one artist and then copied by subsequent artists. To add to the confusion, paintings could often be a collaborative effort where one painter would paint the head while another would paint the clothing and perhaps another background. (I wish I had such an assistant...I hate painting backgrounds.) Unfortunately, we have no record of Sofonisba having an assistant, but Philip did hire Coella to copy several of Sofonisba's works. This painting may have been a copy of a lost original.

Elizabeth gave birth to two children and the first, the Infanta Isabella Clara was to become a lifelong friend to Sofonisba and Philip's favorite daughter. (shown here. She is the one of the left) Sadly, Elizabeth's third pregnancy became her undoing. In 1568, she died during a miscarriage after suffering from several weeks of nephritis (possibly a kidney infection caused by her pregnancy?). Sofonisba must have been heartbroken over the death of her confidant and queen, as was Philip. The workaholic king was said to have loved Elizabeth the most out of any of his wives and he went into a deep mourning after her death.

Philip's third wife was Anne of Austria, (shown left) the daughter of Maximilian II, described as, "a plain girl with a good complexion, gentle, kind, dull, and as devout as Philip himself".(5) Around 1570, shortly before Philip's marriage, he arranged a marriage for Sofonisba to a noble Sicilian named Don Fabrizio de Moncada. Sofonisba may have painted the below marriage portrait of her and Don Fabrizio, but the portrait is currently attributed to an unknown artist. The women in the portrait is the correct age and she does have the exact same dimpled chin and ears as Sofonisba's earlier self-portraits.

Sofonisba and her husband stayed in the Spanish court for about 18 years until around 1578 when they traveled back to Palermo. The following year, Don Fabrisio died from a "violent disease," possibly another plague traveling through Italy. Sofonisba was then recalled to Spain, but she had other ideas. She decided she was going home to Cremona. The rest of Sofonisba's life could read like a Harlequin Romance except many of the details of her life are lost. What we do know is that on her journey home, she fell in love with a much younger ship's captain named Orazio Lomellino. Around 1580, they were married and moved to Genoa. The marriage had to be a happy one because it lasted 40 years.

In Sofonisba's later years, she painted several religious painting including Saint Francis, Lot with his Daughters, and Saint John the Baptist in the Desert. Unfortunately, these paintings are lost. The painting shown here, Madonna Nursing Her Child was once attributed to Luca Cambiaso until it was cleaned in 1967 and a faint signature emerged - "Sofonisba Lomellina Anguissola Pinxit, 1588". Art historians have described this painting as "Mary looks down lovingly at her son". (6) It could be that it has lost some details in the restoration process, but I just don't see that. To me, Sofonisba's Madonna looks like she is wistfully day dreaming and not really paying attention to the baby at her breast. As any nursing mother knows, if you are not totally focused on a baby when nursing....they can sense it. If you look closer, that baby is just about to do that thing babies do to get their mom's attention. ouch!

A painting that I think better shows Sofonisba's attention to human emotion is Holy Family with Saints Anne and John. (shown below)

I love the way the older woman is looking at the child. She seems to be reflecting on her youth. Notice the man in the background. Could he be a reminder of time passing? And look at the adorable little dog curled up in the corner. Sleeping dogs typically are incorporated into Renaissance paintings to honor the deceased. Perhaps this painting was an ode to one of her younger sisters or maybe the children she never had. (7)

Sofonisba later retired to Palermo when her failing eye sight prevented her from painting. During her retirement, van Dyck painted his famous portrait of her that would later be copied by several artists. Annibale Caro said that, "there is nothing I desire more than an image of the artist herself, so that in a single work I can exhibit two marvels, one the work, the other the artist." (8) He was never to get his wish. The following year, Sofonisba died in 1625.

Sofonisba sketches continued to circulate throughout Europe and would inspire many other female artists including Lavina Fontana, Narbara Longhi, and Fede Galizia. Vasari said of Sofonisba that she, "has worked with deeper study and greater grace than any woman of our times at problems of design, for not only has she learned to draw, paint, and copy from nature, and reproduce most skillfully works by other artists, but she has on her own painted some most rare and beautiful paintings.”(9)

Currently, Wikipedia states “van Dyck and his exact contemporary Velázquez were the first painters of pre-eminent talent to work mainly as Court portraitists.” If you could step back in time and ask van Dyck if this statement was true, I think he would have a more humble answer. He could have told you about Sofonisba Anguissola, a protrait painter he met in his youth, who inspired him and countless other artists to bring grace and sensitivity to Renaissance portrait painting.

Notes:

(1) Perlingieri. p. 204

(2) Perlingieri. p. 77

(3) Perlingieri. p. 72

(4) Vasari. p. 202

(5) Perlingieri. p. 143

(6) Perlingieri. p. 178

(7) Sofonisba's sister, Lucia Anguissola was also a talented painter, but many of her works are lost.

(8) Jacobs. p. 1-2

(9) Vasari p. 343

Sources and Futher Reading:

Vasari, Giorgio. Lives of the most eminent painters, Volume 2, New York: NY, Simon & Schuster, 1946.

Perlingieri, Ilya Sandrea. Sofonisba Anguissola, The First Great Woman Artist of the Renaissance, New York: NY, Rizzoli, 1992.

Charles de Tolnay. "Sofonisba Anguissola and Her Relations with Michelangelo" The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery, Vol. 4 (1941), pp. 114-119.

Frederika H. Jacobs. "Woman's Capacity to Create: The Unusual Case of Sofonisba Anguissola", Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 47, No. 1 (Spring, 1994), pp. 74-101.

A nice collection of Sofonisba works can be seen here and also at the Artchive